IFA IN CUBAN MIAMI

To appreciate the containment of Abakua lodges to particular port cities of western Cuba-in spite of the global travels of its members as well as the kua group desire of some to establish lodges abroad-it is instructive to note a paral tyof these lel movement in the Yoruba-centered Cuban practice of Ifa, noting that its an groups reestablishment is a simpler process. Like Abakua, Ifa is thought to have been established in Cuba in the first half of the nineteenth cent~ry. 32 Before the {oruba Ifa 1959 Revolution, the estimated two hundred babalawos in Cuba all knew each other. 33 By the 1990S, leading Cuban babalawos gave me estimates of ten thou Cuban sand to describe their numbers, and neophytes were arriving from throughout nsmis the Americas, Europe, and elsewhere to receive Ifa consecrations and travel [)IDe to home with them. lOt the In 1978, highly specialized Ifa ceremonies performed in Miami were geared lict the to reproduce there the foundation of Ifa in Cuba some 150 years earlier.34 The in the ceremonies were led by Nigerian babalawo Ifayemi ElebU.ibQn Awise (chief Ifa In this priest) of Osogbo, who traveled to Miami for the occasion.Two of the partici knows pating Cuban babalawo were also Abakua leaders, Luis Fernandez-Pelon, who IlS. Be 35 was initiated as a babalawo in Nigeria, and Jose-Miguel G6mez, both of whom Ie with are cited in this study.36 This Ifa reestablishment ceremony was led by one babalawo, while Abakua consecrations involve scores of initiated men acting in concert, in addition to the required tributes paid to the existing lodges in Cuba. Jose-Miguel Gomez was an Abakua leader who ran for the political office of councilman in Sweetwater, Florida, in 1991. Gomez was the Mokango of his lodge Ebian Efa from 1926

to 2003, Mokango being one of the four lead ers of an Abakua lodge. Gomez lived to be the eldest holder of this title in his generationY He was also a babalawo, as well as a leader of Cuban-Kongo prac tice: Padre Enkiza Plaza Lirio Mama Chola, Templo #12, Santo Cristo del Buen Viaje. Gomez left several unpublished essays about Abakua history in Cuba and Africa. He thus exemplified Abakua activity in Florida: he did not create a lodge or lead ceremonies, even though he was a master; instead, he studied the Cuban past and African mythology while passing it on to fellow initiates.

ABAKUCI ACTIVITY IN MIAMI, TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

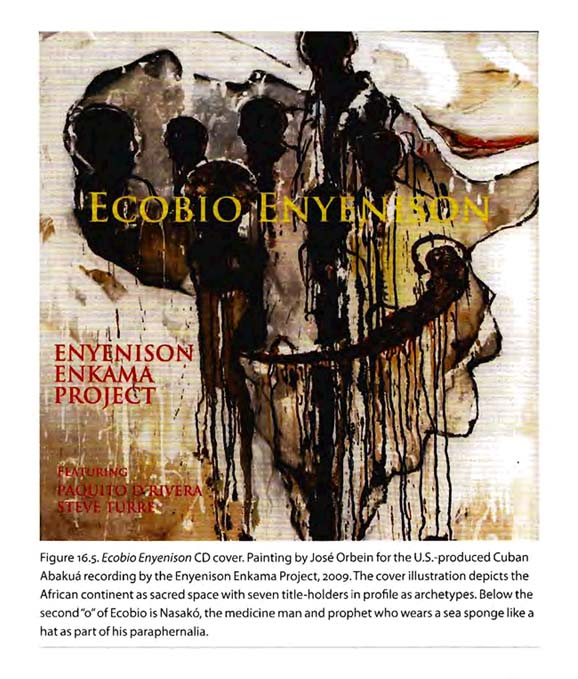

Abakua activities in Miami in the first decade of the twenty-first century have been ignited by recent face-to-face encounters between Abakua members and their Nigerian and Cameroonian counterparts in the United States. These encounters began in 2001 when an Abakua performance troupe participated in the Efik National Association of USA meeting in Brooklyn, New York. In 2003, two Abakua leaders traveled to Michigan to meet the Obong (Paramount Ruler) of Calabar during another Efik National Association meeting. In 2004, two Abakua musicians traveled to Calabar, Nigeria, to participate in the annual International Ekpe Festival. In 2007, an Ekpe troupe from Calabar and an Abakua troupe performed together onstage in Paris for five concerts celebrating their common raditions. Then in 2009, those Abakua living in the United States who went to Paris produced a CD recording that fused music and ritual phrases from both groups. Called Ecobio Enyenison, “Our Brothers from Africa,” it also included the participation of a Cuban artist named Jose Orbein, whose painting appears on the jacket (fig. 16.5), and an Abakua singer named Angel Guerrero, both based in Miami. All of this activity has energized Abakua communities in Miami, where Guerrero has also acted as an entrepreneur by sharing information about African Ekpe with his ritual brothers and organizing them in cultural events that have been advertised on the internet and recorded in video programs.

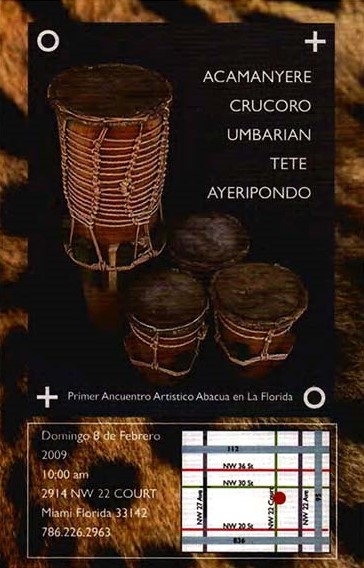

The first cultural event in Miami was billed as an “Abakua fiesta” (party or feast) to ensure that it was not misinterpreted as an initiation ritual (fig.16.6). It was held on February 8,2009, in a private home with a large patio to accommodate the drumming, dancing, and food preparations where hundreds gathered. A second party was held on August 2, 2009, to celebrate Guerrero’s birthday. After these general events for the entire community, members of particular Cuban lodges living in Miami began to celebrate the anniversary of their lodge’s foundation. On February 24, 2010, the members of the lodge Itia Mukanda Ef6 gathered with friends to celebrate the anniversary of their founding in 1947 in Havana.

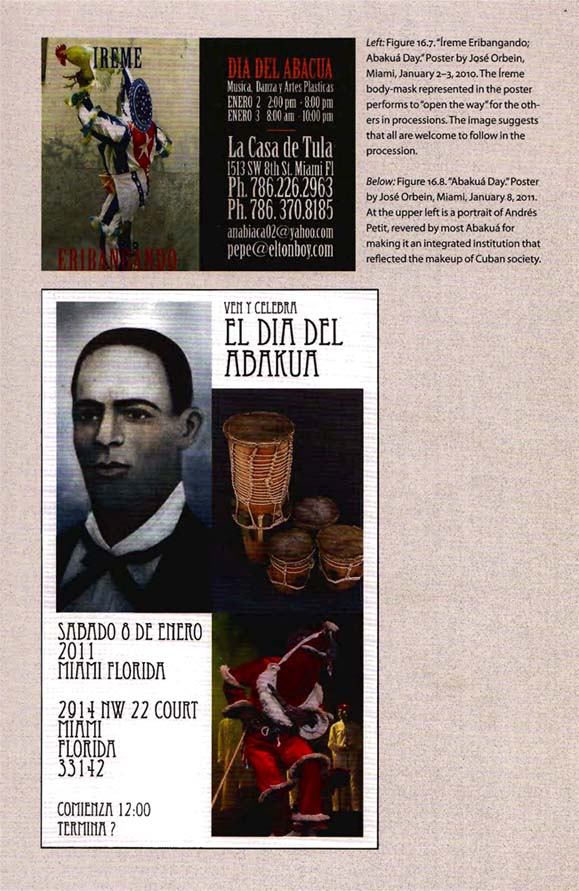

On January 2 and 3, 2010 , in Miami, members of two Havana lodges from the same lineage, Efori Enkomon (founded 1840) and Ekue Munyanga Ef6 (founded 1871), celebrated a feast to adore the La Virgin de la Caridad (the Virgin of Charity), the patron saint of the Munyanga lodge and also of the Cuban nation (fig. 16.7). This saint is popularly understood as a dimension of Ochun,the Lukumi/Yoruba goddess of fertility, who for Abakua also represents Sikan, their Sacred Mother.This date was chosen for being a weekend near January 6, known as “Abakua day,” the anniversary of the colonial-era Three King’s Day processions wherein African “nation-groups” would perform their traditional dances and greet the governor general in Havana. This day was chosen to found the Abakua society in Cuba because they were able to use the mass celebration as a cover for their own activities. On September 14 and 15, 2010, members of the Havana lodge Amiabon (founded in 1867) gathered, apparently for their own anniversary (fig. 16.7). The most recent feast was “Abakua day” on January 8, 2011, in Miami at a private home (fig. 16.8).

These activities have been meaningful to Abakua on either side of the “Rum Curtain.” Angel Guerrero (2011) reported that Abakua had little opportunity to communicate across the Gulf Stream from the 1960s to the 1980s: “Because of the rupture in communications between those who left and those who stayed, many members willing to send money to help their lodges in Cuba were impeded. Also,many Abakua lodges performed ceremonies without knowing that some of their brothers in exile had passed away.” In Cuba, as in West Africa, when a lodge member dies, all lodge activities are suspended until the proper rites are enacted. In the United States since the first decade of the twenty-first century, Guerrero reports: Now with mobile phones, faxes and internet we receive news instantly.Experience has taught me that the links between Abakua members obliges one to see the condition of exile in a specific way. Our solidarity makes us think about how we can help our brothers so that they have a more dignified life, because in essence this is part of the oath we made upon initiation in the society Ekoria Enyene Abakua [full name of the AbakuaJ. Through all the gatherings so far here in Miami our greatest achievement has been to gather and unite all those brothers who had been divorced from their lodges in Cuba, so that now they are actively supporting their lodges. Thanks to Abasi [Supreme BeingJ this achievement has already benefited many lodges in Havana and Matanzas. Today we are stronger than ever, because “In Unity, Strength!” Abakua gatherings in Miami were inspired by the recent communication with African Ekpe members; contact with Africans confirmed that their inherited lore really did come from African masters. In other words, instead of simply assimilating into the values and systems of North America and forgetting their past, many Abakua have opted to accept responsibility for their oaths of solidarity, thus renewing ties with their Cuban lodge members. Instead of an abstract or nostalgic relationship to African Ekpe and Cuban lodges, Abakua in Miami are emerging as actors in an international movement within the Ekpe-Abakua continuum of exchanging ideas, and of reassessing the values of their inherited traditions for the identity of their communities.

DECEPTIONS OF ABAKUA BY ARTISTS IN FLORIDA

From the late nineteenth century to the present in Cuba, there has existed anartistic tradition of using Abakua themes in music, theater, and painting as a symbol of the Cuban nation itself. This tradition has continued among Cuban artists living in Florida today.

Mario Sanchez (1908-2005) is an early example of an artist working in Key West who documented carnivalesque popular dances in the early twentieth century. Because he depicted various styles of body-mask performance, includingAbakua heme and Puerto Rican Vejigantes, some scholars interpreted this as evidence for Abakua rites occurring in Key West.Sanchez was more likely exploring issues of identity and cultural performance, as did other artists mentioned in this essay. Artists have been creating images of freme for numerous purposes, none of which provide evidence for Abakua ritual activity in Florida. Instead they are examples of artists honoring their Cuban traditions,their memories of Cuban identity, and so on. The next three artists (discussed below) are not Abakua members, yet as males from the western part of the island where Abakua is practiced, they understand its important role in Cuban history and identity and incorporate Abakua motifs in their work. Some have gone further to study the literature, especially that of Lydia Cabrera.

In addition to promoting Abakua events artistically, Jose Orbein (b. 1951) has painted many series depicting esoteric aspects ofAbakua tradition. Living in Miami, Orbein was born and raised in the Cayo Hueso neighborhood of Havana, a barrio named in homage to the exiled Cubans living in Key West who supported the independence movement against Spain in the nineteenth century. Orbein wrote: “Now living in Miami, I’m using influences of the Abakua in my canvases. I’m a strong believer of the society who was raised admiring and respecting all the Efori Enkomon ekobios [brothers] of my neighborhood Cayo Hueso in La Habana, that includes some of my family and close friends.My ancestors came from the Calabar region in Africa; I know this because my

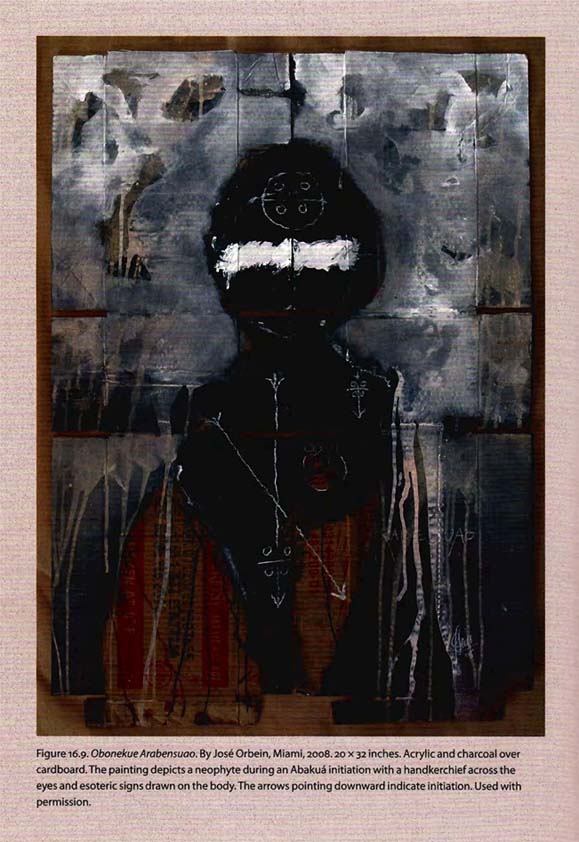

grandmother used to keep a log of the lineage of my family dating back to enslavement.” The ties of Calabar and Abakua to Orbein’s family and community have generally inspired his creative process, but his collaborations in Miami with Abakua singer Angel Guerrero have led to a series of Abakua themes with specific imagery and titles based upon deep knowledge. For example, Orbein’s Obonekue Arabensuao (fig. 16.9), painted in Miami in 2008, depicts an Obonekue neophyte undergoing initiation with the arabensuao mystic circle drawn on the head.

Another work, Enkiko Nasak6 Murina (2009), refers to the presence of the rooster during the initiation process (ekiko is “rooster” in the Efik language of Calabar). In southwest Cameroon, Nasak6 is remembered as a prophet from the region of Usaghade where Ekpe was legendarily founded centuries ago. The painting depicts five neophytes blindfolded during initiation, with a rooster, next to a sacred ceiba (kapok) tree with three dimensional thorns.The painting Iyamba Quifiongo (2010) represents the Iyamba (a lodge leader) and his signs of ritual authority. This work demonstrates that Orbein is also informed by the publications of Lydia Cabrera, in this case Anaforuana (1975), about the ritual signatures of the society. Whereas Iyamba is the title for a lodge leader in the Calabar region, Kinyongo is derived from the Efik phrase keenyong,meaning “in the sky,” which could be interpreted as “Iyamba has powers from the sky” or “Iyamba is the highest.

Orbein was also a promoter of the Abakua feasts organized by Guerrero in Miami from 2009 to the present, through creating poster advertisements.His poster for the 2009 event presents the Abakua phrase “Akamanyere crucoro umbarain tete ayeripondo,” meaning “welcome all as a great family,” while announcing “the First artistic gathering of Abakua in Florida” (fig. 16.6). The map identifying the location of the feast is a sign that these activities promote educationabout Abakua practice as a community-wide event, instead of being a “secret, hidden” one that in the past may have aroused suspicion among non-members. The process of communicating with West African

counterparts is fueling desire for a wider public understanding, so that the ongoing public performances already mentioned will be popularized as relevant to all in the transatlantic African diaspora, as well as the Cuban diaspora. The 2010 poster displays the “Ireme Eribanganda,” a body-mask used to lead processions during initiation ceremonies, implying that “Abakua is moving forward” (fig. 16.7).The use of the colors and star of the Cuban flag are another statement that Abakua is “as Cuban as black beans and rice.” Participants have reported that in Cuba, the use of a Cuban flag on an Ireme could lead to conflicts with the authorities, a reminder that Abakua jurisprudence has acted independently from the colonial Spanish and Cuban state since its foundation. The 2011 poster celebrates the legacy of nineteenth-century Abakua leader Andres Petit through his portrait (fig. 16.8). In the 18sos-60s Petit lead the successful process of initiating the first white Abakua members, thus ensuring that Abakua would be open to all eligible males of any heritage.

Painter Elio Beltran (b. 1929) was born and raised in RegIa, a small industrial town on the Bay of Havana where Abakua was founded in the 1830s. Still a vital center for African-derived community traditions, RegIa is home to scores of active Abakua lodges. From his home in Florida, Beltran wrote: “I grew up registering dream-like images in my mind during my childhood years. Images that many years later would emerge as oil paintings to help me to ease my pain of separation from the very dear surroundings and people that I loved in Cuba.” A series of paintings reflect the impact of an Abakua heme (body mask) performance on the young artist. Asustados Intrusos, or “Scared Intruders” (1981), depicts “three scared kids hiding and secretly watching an Abakua initiation in the early 1940’S behind the tall grass at the edge of a cliff in the night.I believe it was the Otan Efa brotherhood of the Abakua on the out skirts of my hometown Regla.I was one of the three boys overlooking the scene of the celebration on the site at the entrance to what was known then as El callej6n del Sapo.” A second painting, Ceremonia Secreta (1987), depicts the same event from 180 degrees (fig. 16.10). These paintings are remarkable for depicting how a hermetic club became famous among non-initiates who were awed by the communal rites.

A third painting, Memories del Carnaval (2010, not illustrated here), reconstructs the night scene of a Carnival celebration in an Old Havana neighbor hood circa 1938-40. It shows how elements of African-derived traditions (an Abakua mask, a bata drum, a conga drummer with the camisa rumbera [fluffy 1 sleeves] of early rumba players) were fused in the citywide celebrations. In all of these works, one senses the profound impact of an Abakua mask performance on the young viewer, as well as the identification of Abakua as part of the national culture.

Beltran’s corpus recalls the reaction of Spanish poet Garda Lorca to an Abakua performance during his visit to Cuba in 1929-30. About it, Lydia Cabrera wrote,”I do not forget the terror that the ireme instilled in Federico Garda Lorca, nor the delirious poetic description he made for me the day after witnessing a plante [ceremony]. If a Diaghilev had been born on this island, surely he would have made the diablitos [iremel of the iidfiigos parade through the theaters of Europe.” While Beltran has worked primarily from his memories and in isolation, other painters have consulted with Abakua members during their creative process.

A multidisciplinary visual/installation and performance artist, Leandro Soto (b. 1956) was a leading figure in Cuban art in the 1980s and among the first artists in his generation to explore Afro-Cuban themes. Based in Miami since the 1990S, Soto began to work with Abakua imagery in the first decade of the twenty-first century after learning about the Kachina body-masks of Hopi people of the American Southwest. He created a series of video-installation performance pieces with Abakua imagery that presented the artist as an Abakua mask-here a symbol of Cuba itself-who encounters a kindred tradition in North America.Soto’s Abakua series generally celebrates motion through Abakua body-masks and coded symbolism imagery (fig. 16.11; see detail in fig. 3.3). During this process, Soto conversed extensively with Angel Guerrero,studied Lydia Cabrera’s publications, and also reproduced nineteenth-century Abakua signatures for Miller’s book on Abakua history, The Voice ofthe Leopard (2009)

CONCLUSIONS

It is remarkable that the Abakua cultural movement has been able to expand from ritual secrecy in Havana and Matanzas onto the global stage of performance in the process of communicating meaningfully with African practitioners of Ekpe-the source tradition from which it was separated some two hundred years ago.

As with other cases of oral transmission across long time and space intervals, such as the Vedic and Homeric poems, the Abakua example combines intensive artistic discipline with a ritualized guild framework. As the present moment of history is witnessing the reconnection of the two ends of this vast diasporal arc, the impact of this encounter on the local communities of practitioners is fascinating to observe. At the same time, the public nature of the new encounter is eliciting unprecedented openness to scholarly access,which promises to enrich the description of each of the local traditions that were heretofore so closely guarded from outside view. This chapter documents the participation ofAbakua members in Florida in this process, as well as their allies in the arts who honor and celebrate Abakua as part of an overall Cuban national identity. Eventually, the global Ekpe-Abakua network may develop its own organic scholarship from within, such has happened already to an extent with the Yoruba-Lukumi tradition.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

Thanks to Amanda B. Carlson and Robin Poynor for their support of this project as well as their fine editing. Thanks also to Norman Aberley (curator of the Key West Art and Historical Society), Nath Mayo Adediran (director of National Museums, Nigeria), Peter Appio, “Chief” (engineer) Bassey Efiong Bassey, Elio Beltran, George Brandon, Orlando Caballero, Osvaldo Caballero, Jill Cutler, Senator Bassey Ewa-Henshaw, Luis Fernandez-Pelon, Liza Gadsby, Susan Greenbaum, Angel Guerrero, Stetson Kennedy, Chester King, Victor Manfredi, Jose Orbein, Louis A. Perez, Gerardo Pazos, Leandro Soto, Robert Farris Thompson, and Brian Willson. Thanks to the J. William Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board for a Fulbright Scholars Grant to Nigeria (2009-11) and to Professor James Epoke-the vice chancellor of the University of Calabar.

Thanks to the National Museum of African Art (NMAfA), Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, D.C., for a Senior Fellowship (2011-12).

NOTES

- The leopard society has many names depending on the local language, including Nyamkpe (in Cameroon), Banko (in Equatorial Guinea),Okanka (in Igbo), and Abakua (in Cuba). Most West African communities also recognize the term Ekpe, since the lifik influence in the region was widespread in the nineteenth century.

- Roche y Monteagudo, La policia y sus misterios en Cuba, 27. All translations from Spanish to English are by the author.

- Since the first Ekpe-Abakua meeting in Brooklyn, New York, in 200~, I have discussed this issue with many Ekpe titleholders from the Calabar and Cameroon region now living in the United States.

- The group who call themselves “Ekpe USA” is led by “Sisiku” E. Ojong Orok, “Sesekou” Joseph Mbu, “Sesekou” Solomon Egbe, and “Sisiku” Mbe Tazi, among others. Because of their authority as Ekpe leaders in their villages in Cameroon, they have been able to establish at least one lodge, cautiously following the protocols of this institution.

- An 1882 publication on “The Criminals of Cuba” began a chapter on the “Nyanyigos” by stating: “The police have worked hard to eradicate the nyanyigos” (Trujillo, Loscriminales de Cuba, 360). A ~90~ publication on Spanish penal colonies stated: “Finally, the nyanyigo was conceived of as a dangerous being, shown clearly by the mass deportations during the last period of our dominion, that accumulated a large number of nyanyigos in Ceuta, in Cadiz,and in the Castle of Figueras” (Salillas, “Los fiafiigos en Ceuta,” 339).

In 1925 a study of the history of RegIa, the birthplace of Abakua in Cuba, had a chapter called “Criminality and Nyanyagismo in RegIa” (Duque, Historia de Regia, 125-27). A 1930 publication in Cuba asked rhetorically if Abakua was related to “abominable crimes”: “In Cuba, are witchcraft and nyanigism religious practices or black magic? … Is it true that they shelter organizations dedicated to the most abominable crimes?” (Martin, Ecue,chango y yemaya, 7). This contextualization of Abakua continues into the present. In 2011 in Havana a monograph was published with the title “The Abakua Society and the Stigma of Criminality” (Perez-Martinez y Torres-Zayas). - Marti, “Mi Raza”; Marti, Our America, 313 .

- The Havana lodge Bakoko Efo, mentioned above, was specifically responsible for organizing the entry of European descendants into the Abakua society (cf. I. Miller, Voice of the Leopard).

- For details see I. Miller, Voice of the Leopard, 137-39

- In Calabar and nineteenth-century Cuba, Abanekpe was an Ekpe term for first-level initiate. Cuban Abakua use the variant terms abanekue and obonekue .

- An 1881 source refers to the payment of fees to create Cuba’s first lodge, a process consistent with Cross River and later Cuban practice. Rodriguez, Resefia historica de los fidfiigo s de Cuba, 5-6.

- R. Cabrera, Cartas a Govin, 3-4. R. Cabrera was the father of the eminent Cuban folklorist Lydia Cabrera.

- F. Ortiz, Los instrumentos de la mrisica afrocubana, 5:301. Ortiz wrote that the reed “gave some notes in antiphonic form so that the multitude would respond in chorus with his chants.” Ibid., 309.

- Kennedy reported: “Nanigo came to Florida for various reasons. There were naturally some Nanigos among the Cubans who immigrated first to Key West and later to Tampa, seeking employment in the cigar factories and other industries. Others were revolutionary patriots seeking refuge from the tyranny of Spain.” “Nafugos in Florida,” 154-55.

- “Lo que extraemos de su lectura [de Kennedy y Wells] nos lleva a la certeza de la existencia de iaiiigos [en Key West].” Sosa, “Naiiigos en Key West,165.

- Wells, Forgotten Legacy, 48.

- Kennedy, “Naiiigos in Florida,” 155 .

- Interviews with Gerardo “EI Chino” Pazos, in Havana.

- Telephone conversation with Stetson Kennedy, April 2002. Kennedy referred to his lack of fluency in Spanish. Describing research among a Cuban family in Tampa, he wrote: “When the cooking is over and the meal placed on the table, there is a sudden burst of very rapid and excited Spanish which I am unable to understand” (“All He’s Living For,” 21). In a letter to the author, Kennedy (2002) wrote: “I do not know much about naniguismo beyond what I have read in Dr. Fernando Ortiz’s Los Negros Brujos … and my own article.” In his next letter, Kennedy (2002) wrote: “I do not now recall the contents of my nanigo article, or whether it even implied that there might have been nanigo organizations in Florida. I suspect that it would be difficult to prove either that there had been, or had not been.”

- “Recent folklore recording expeditions conducted by the Florida Work Projects Administration of the Library of Congress located a number of people in Key West and Tampa, besides those already mentioned, who undoubtedly have an initiate’s knowledge of Nanigo, obtained both in Cuba and locally…. But because of their extreme poverty,they refuse absolutely to perform without some pecuniary remuneration-which unfortunately was unavailable to the WPA expeditions” Kennedy, “Naiiigos in Florida,” 155). If Abakua groups did exist in Florida, they would have performed ceremonies, aspects of them public, to which WPA researchers could have gone. Lacking such groups, there was only “fragmentary mention” of a masked dancer and a bongo. I did locate testimonies of Cubans and Spaniards who had lived in Cuba, Key West, and Tampa, conducted in Ybor City and Tampa in the late 1930S. The Federal Writers’ Project Papers housed in the University of North Carolina Library at Chapel Hill contain descriptions of cigar workers born in Havana and living in Florida; none of them refer to the Abakua.

- Florida: A Guide, 133.

- Historian Louis A. Perez Jr., letter to the author, 2004.

- E-mail to the author from Professor Greenbaum, 2003.

- Sosa, “Nafiigos en Key West,” 166-67.

- Marti, “Una orden secreta de africanos,” 324; Muzio, Andres Quimbisa, 71-72; Sosa, “Nafiigos en Key West,” 167; Ishemo, “From Africa to Cuba,” 256. Jesus Cruz (personal communication, 2000), Ekuenyon of the Ordan Efi lodge in Matanzas told me that he had heard that Tomas Sur! was Abakua but that his lodge name was not known. After reading Sosa’s essay, Cruz responded that nothing in this article proves that Abakua conducted ceremonies in Florida, nor are such activities known about by Abakua leadership in Cuba.

- In spite of the errors in this essay, Sosa should be praised for his support ofAbakua culture in Cuba in the early 1980S in the form of his book (Los afiigos), since it was an unpopular theme in the political sphere at the time.

- Ishemo, “From Africa to Cuba,” 268. Ishemo falsely cited Muzio (Andres Quimbisa, 71) and Helg (Our Rightful Share, 87); there is no mention in either of Marti, a Famba, or a flag. Ishemo also cited Sosa (“Nafiigos en Key West,” 167-68), who in turn cites Marti (“Una orden secreta de africanos”), but Marti made no mention of Abakua. Marti wrote of a secret society of Cuban “Africans,” who had given up the drum in order to learn to read-a non sequitur-and whose reunions took place in a “bannered hall … the hall whose parties were adorned with the banner of the revolution” (“sala embanderada … la sala que adorna sus fiestas con la bandera de la revolucion”) (“Una orden secreta de africanos,”324). Sosa imagined that Marti wrote of an Abakua group in Key West. Ishemo’s piece is riddled with the uncritical repetition of errors, and poor translations.

- Ayorinde, “Ekpe in Cuba,” 141.

- Ayorinde quoted Brandon (“The Dead Sell Memories,” 108). Brandon (2011 personal communication) confirmed that he made no such claim and that this was a misquote.

- Luis “el Pelon” died in 1997 in Miami; his body was carried to Havana to receive Abakua ceremonies and burial. Ceiba (Kapok, or White Silk Cotton Trees) are “venerated and revered in forests zones of Nigeria. It is a fetish tree and sacrifices for the release of people captured and detained in the world of witches and wizards ready for the kill are performed at the base of this large tree” (“Nature Trail Tree List,” 3) .

- Cf. 1. Miller, “Obras de fundacion: La Sociedad Abakua.”

- I was shown a copy ofthis letter in the office of Mr. Angel Freyre “Chibiri,” president of the Abakua Bureau (la Organizacion para la Unidad Abakua), in RegIa in 2000.

- Cf. D. H. Brown, Santeria Enthroned, 78; Ortiz reported the founding of Yoruba derived Bata drums in Havana in the 1830S (Los instrumentos de la musica afrocubana, 31516).

- “There are said to be about two hundred true babalawo in Havana, and most of them have been drawn to the large cities where they can earn more money.” Bascom, “Two Forms of Afro-Cuban Divination,” 171.

- The ceremony performed was the creation in Miami of the first Olofies, a ritual vessel possessed only by high-ranking babalawo. A 1978 Miami newspaper article reporting on the event stated that the first Olofies were made by Yoruba babalawos in Havana more than “200 years” before. Archives of Luis Fernandez-Pelon.

- Thanks to Mr. Nath Mayo Adediran (2005 personal communication), for the cor rect title and spelling. For a detailed report on this process see D. H. Brown, Santeria Enthroned, 93-95.

- From a Miami newspaper article published in 1978, in the archives of Luis Fernandez-Pelon. There I saw and videotaped a photograph of Luis Fernandez and two other Cubans in O~ogbo, Nigeria, in 1978, taken during their initiation as babalawos there. I also saw a photograph of Ifayemi EI¢buibon dedicated “To my godson Jose-Miguel G6mez”(Caballero, 2005 personal communication).

- David Brown reported that Gomez was initiated into the Lukumi Ocha system in 1929 (Santeria Enthroned, 160). This is consistent with the early Cuban tradition that eligible males should be initiated into Abakua and Palo Mayombe before entering the Lukumi tradition. One interpretation of this tradition is that the “Carabali” (from Calabar) and Central African “Kongo” people arrived to Cuba and other American regions before the Yoruba/Lukumi.

- David Brown reports that Gomez was “the first Cuban-born babalawo to have made Ifa in the United States” (Santeria Enthroned, 325 n. 92). The Cuban-Kongo lineage called Santo Cristo del Buen Viaje was organized by Andres Petit in the mid-1800s (cf. Cabrera, La Regia Kimbisa del Santo Cristo del Buen Viaje).

- In this era in Cuba, February 24 was a national holiday-thus a day free from work-to celebrate the “El grito de Baire” (the Cry of Baire), the commencement of the final war of independence in 1895 by the Cuban rebels against Spain. Being a carnival day in the 1890S, this date was chosen to start a rebellion under the cover of a mass celebration.

- See chapter 17 in this volume on Lucumi crowns.

- Sanchez created “Manungo’s Diablito Dancers” in the 1930S to depict Sanchez’s memories of the “fidfiigo street dance” in 1919. Some scholars thought that this was an Abakua performance, but in fact the body-masks were Puerto Rican Vejigantes, not Abakua. The work represents a street jam session with a bongo player, a trumpet player, and two body-masquerades, in the context of carnival. 1. Miller, Voice of the Leopard .

- Louis Perez (2006 personal communication); Orovio, EI carnaval babanera, 85. The name Key West is an English gloss upon the earlier Spanish name, Cayo Hueso. The Cuban communities of Cayo Hueso in Florida actively countered the Spanish regime. Le Roy y Galvez, A cien afios del 71, 58; Foner, Antonio Maceo, 120; Montejo-Arrechea, Sociedades negras en Cuba,104.

- E-mail message from Jose Orbein to the author, September 2007 .

- Cabrera documented a version of this term: “Biorasa: circulo que se dibuja en la cabeza del neofito para ser iniciado.” La Lengua Sagrada de los afiigos,112 .

- The BoNasako family, meaning “the family of Nasako,” presently lives in Ngamoki within the Ekama community of Ngolo-speaking people of the Rumpi Hills in Cameroon.

Thanks to Mr. Nasako Besingi of Mundemba, as well as Mr. Kebulu Felix of Limbe and their extended families, Cameroon, the author attended BoNasako family reunions in Ngololand in February 2011 and March 2012. - For details see chapter 4 of 1. Miller, Voice of the Leopard, 103-18.

- Chapter 2 of Beltran’s autobiography Back to Cuba tells this story.

- Otan Ef6 was founded around 1909 in Regia. Lydia Cabrera wrote: “Otan Efor … of Regia. Ancient Potency.” La Lengua Sagrada de los Nafiigos, 465.

- Cabrera, “La Ceiba y la sociedad secreta Abakua,” 35; Cabrera, El Monte, 217.

- Cf. 1. Miller, “Abakua: The Signs of Power.” Soto titled these performance pieces Efi Visiting the Desert (after the Efik people of Calabar who helped create Cuban Abakua) and Kachireme, a fusion of the Hopi Katchina and the Cuban ireme body-mask. See the artist’s gallery at https://www.leandrosoto.comlkachireme-efi-visiting-the-desert.html.