Home >EFIKS of the New World > EFIK Cubans

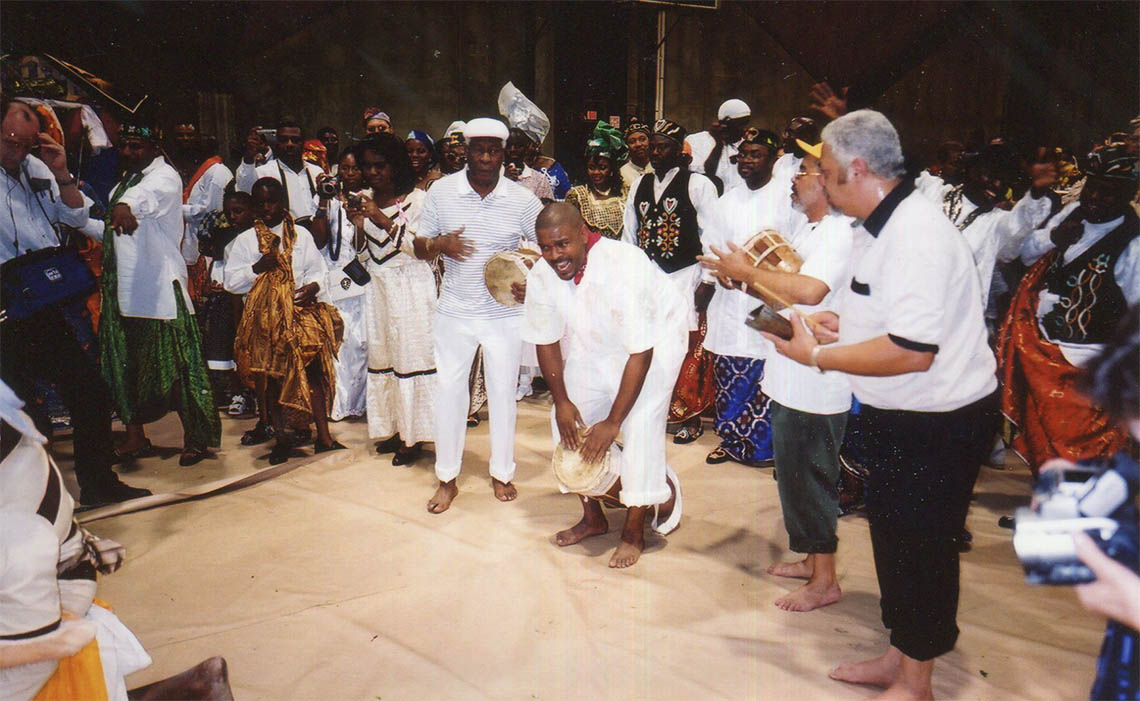

Efik cubans Performing at ENA convention Pratt Institute New York , 2001

Abakua Communities in Florida

Members of the Cuban Brotherhood in Exile

Prof . Ivor L. Miller

The Abakua mutual-aid society of Cuba, re-created in the 1830S from several local variants of the Ekpe leopard society of West Africa’s Cross River basin,is a richly detailed example of African cultural transmission to the Americas. Since the late nineteenth century, many Abakua members have lived in Florida As part of the larger Cuban exile community. While focusing on the Florida ex perience, this essay discusses Abakua historically, since there exist structural relationships between its lodges, as well as spiritual connections among its membership that extend from West Africa to the Western Hemisphere.

Abakua leaders who migrated from Cuba have regrouped in exile and maintained their identity as Abakua, but due to their strict protocol they did not sponsor lodges outside of Cuba. Therefore the Abakua communities in Florida gather for commemorative celebrations but do not perform initiations, which are performed only in their home lodges in Cuba. Due to renewed communication with African counterparts through a series of meetings in the United States, Europe, and Africa since 2001, Abakua activities-including rumbas and commemorative social gatherings-have intensified in the first decade of the twenty-first century. Meanwhile, vibrant expressions of Abakua prac tice have been produced by Cuban artists in Florida through representational paintings that depict Abakua as integral to a Cuban national identity.

EKPE MIGRATIONS, ABAKUA FOUNDATIONS

The Abakua mutual-aid society established by Africans in RegIa, Havana, in the 1830S was derived principally from the male “leopard societies” of the Cross River region of southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon. Calabar, the main port city of this region, is the homeland of three distinct communi ties, known as Abakpa (Qua-Ejagham), Efil.t, and Efik, who call their society.

Ekpe and Ngbe (or Mgbe), after the Efik and Ejagham terms for “leopard.” Although Cross River peoples migrated to many parts of the Western Hemi sphere during the transatlantic slave trade, it was only in Cuba that they suc ceeded in re-creating Ekpe, as far as is currently known.Ekpe was established in Cuba because among the thousands of Cross River People there were included knowledgeable specialists instrumental in organizing their people through the transmission of traditional knowledge. Another important element was the conducive tropical environment with mangrove estuaries similar to that of Calabar. In Calabar, Chief Bassey Efiong Bassey explains,

If you want to plant an Ekpe in some place, there must be an Obong Ekpe [a titleholder] with authority, who is versed in the procedure. In colonial Cuba, it was possible, because some of the people who went were Obong Ekpes who were forcibly taken away. When they got there they knew exactly what to do to plant it. There is the belief that if you don’t have the authority, if you don’t know the procedure inside out, it will lead to death, or you will lose your senses. So people don’t want to do it.

The Cuban leaders have maintained their Ekpe (i.e., Abakua) in their home land, but they have never authorized any member to establish a lodge outside of Cuba. The same is true for contemporary Nigerian Ekpe leaders, who to date have not authorized any lodge to be created outside of Africa.

In West Africa, as in Cuba, the societies are organized through local lodges each with a hierarchy of grades having distinct functions . Because of the obvi ous historic and conceptual links between Ekpe and Abakua, I refer to both as variants of an Ekpe-Abakua continuum that exists in the contemporary regions of Nigeria, Cameroon, and Cuba, all places where lodges are orga nized, although some of their members live outside these regions, including the United States.

As a diaspora practice, Abakua maintains many facets of the Ekpe practice of West Africa from two centuries ago. Abakua leaders transmit inherited his torical information by performing it as “ritual-theater” during ceremonies. All of the roughly 150 lodges in Cuba have traditions of coded language and ritual performance that refer back to West African origins. Cuban Abakua leaders look to the Calabar region with reverence as a historical source and a holy place. For example, Abakua have created many maps that indicate specific places and events in the foundation of their institution in Africa Abakua phrases also refer to African foundations: “Echitube akarnbamba, Efik Obuton?” asks, “How was the first lodge created in Africa?”2 The Efik Obuton lodge of Cuba was named after Obutong, an Efik community in Calabar with a strong Ekpe tradition. This phrase evokes African founding principles in the present. Even with this orthodox sentiment, Abakua leaders acknowledge adaptive innovations in Cuba throughout their history.

Abakua intiations are performed exclusively in Cuba. Those members who live in Florida therefore look to Cuba as a source; their activities celebrate foundational moments in Abakua history, specifically the anniversaries of their particular lodges. This is because in Florida there are no lodges nor initia tions. Throughout the Ekpe-Abakua continuum exists a generalized protocol that new lodges may be established only with the sponsorship of a “mother” lodge, while initiations may only be conducted by specific titleholders working in concert. This protocol has led to the containment of lodges within the spe cific geographical regions of Nigeria, Cameroon, and Cuba.

Nigerian members living in the United States have wanted to establish lodges there, but leaders in West Africa have not yet sanctioned it.Cuban members in Florida also have tried to establish lodges there, but leaders in Cuba have not sanctioned it. In an exceptional case, in the late 1990S several lodge leaders from Cameroon who migrated to the United States began the process of creating a lodge in the Washington, D.C., area in order to pass their authority on to their children also living in the United States. Because this project is ongoing, it will be dealt with in a future publication. The general reluctance to authorize lodges outside of Africa and Cuba is meant to protect the institution by preventing new lodges from acting autonomously outside the jurisdiction of the mother lodges. Though this strict protocol remains, modern communications (letters, telephones, websites, e-mail, and air travel) are being used to bring Ekpe and Abakua members into greater awareness of each other. This new development is reflected in recent cultural expressions ofAbakua in Florida by Abakua leaders, as well as by their allies working in the arts.

ABAKUCI JURISPRUDINCE AND EXILE TO FLORIDA

Abakua members reached Florida from Cuba after their ancestors had initially migrated from West Africa, where Ekpe was a “traditional police” under the authority of the council of chiefs of an autonomous community. Their decrees were announced publicly and their verdicts executed by specific Ekpe grades with representative body-masks (i.e., a uniform that covers the entire body to mask the identity of the bearer). In colonial Cuba, Abakua leadership main tained the prestige of Ekpe through the autonomy of each lodge and the rig orous selection of its members. Because the primary allegiance of an Abakua member was to his lodge and its lineage, Abakua held jurisdiction over its members, a position that conflicted with agendas of the Spanish government. As a result, Abakua has been demonized by various colonial and state adminis trations through much ofits history.s But other narratives maintained by Aba kua leaders represent Abakua as being “tan Cubano como moros y cristianos”

(as Cuban as black beans and rice). These Abakua narratives are persistent ad initially because they coincide with the widespread Cuban ideology that “A Cuban is er the more than mulatto, black, or white,” as famously articulated by Jose Marti, eirdecrees “the apostle of Cuban Independence,” in the late nineteenth century. The deep ties existing between Cuban creoles that transcended race and class were sustained in many cases through membership in Abakua, whose members by the 186os included eligible males of any heritage, making them the first Cu ban institution whose leadership reflected the ethnic diversity of the island,long before the creation of the Cuban Republic. At the onset of the Cuban Wars of Independence (1868), those suspected by colonial authorities of being rebels were sent into exile in Spanish Africa (Chafarinas Islands, Ceuta, Fernando Po [today Bioko] , and other sites); among them were Abakua. To evade possible deportation, many Abakua members fled to Florida as part of a larger Cuban community, creating social networks and cultural imprints acting as that exist to the present.

CONFRONTING MISCONCEPTIONS

Misconceptions and misinformation of African-derived institutions-the rule during the slave trade and colonial period-persist into the present, and Abakua is no exception. Being a self-organized African-derived institution un authorized by colonial authorities, Abakua was misconceived as a criminal or ganization. Later reports about Abakua creating lodges in Florida were simply erroneous. Both errors were documented in twentieth-century literature to the extent that they became accepted as fact.

To outsiders, an African-derived traditions were “black culture,” without awareness of distinctions between communities. Abakua were commonly re ferred to as ndnigos (nyanyigos), a term likely derived from the nyanya raffiachest piece worn on many Ekpe and Abakua body-masks. Distinct African derived practices were lumped together as..

ndnigo by outsiders, but colonial authorities also associated ndnigos with crime. Abakua members have there fore since the early twentieth century rejected this term, using instead “Aba kua,” a term likely derived from the Abakpa (Qua-Ejagham) people of Calabar. The general confusion about ndnigo persists in the literature about Abakua in Florida.

From the 1860s to the present, exiled Abakua members have regrouped in foreign lands. Because of this, some scholars have argued that new Aba kua lodges were re-created in the Cuban diaspora, including Florida. There is little evidence for this. The collective and hierarchical nature of Ekpe in the Cross River region, a structure firmly reproduced in Cuban Abakua, prohibited the informal foundation of new lodges.Certainly, exiled Abakua gathered to share their music, dance, and chanting, but initiations seem not to have been performed, nor were lodges created. Abanekues (initiates) who gathered in exile would not have the authority to form a lodge, nor could they perform ceremonies, since there would have been no sponsoring lodge or group of title holders to direct the rites.

Abakua lore recounts how African ancestors designed a collective that could act only in concert. This practice underscores the profundity of the transfer of Ekpe to Cuba, since this could only have been achieved through the collective action of authorized titleholders and their supporters. Even today, Abakua is the only African-derived institution in Cuba to maintain both a conective identity and a decision-making process affecting the entire membership.

The collective procedure required for the creation of the first Abakua group is repeated throughout the Cuban literature. This includes the payment of fees, the consecration by a sponsoring lodge, and the presence of other lodges acting as witnesses; these are basic to the transmission of Abakua authority.

Abakua members have been present in Florida since the late nineteenth century, yet to date there is little evidence ofAbakua ceremonies for establish ing a chapter being performed there. The earliest known reference to Abakua in the United States was written by Raimundo Cabrera, who described the ar rival of his passenger ship from Havana to Key West in ~892; “Just as the boat came close to the shore, one saw the multitude that filled the wharf and heard the special whistles that came from it, to which were answered others of the same modulation from the passengers who occupied the prow. I realized the meaning of these whistles! They are tobacco rollers from Havana who recog nized and greeted one another. This greeting of fuifiigo origin was imported to the yankee city.”ll Abakua greetings normally consist of coded handshakes and phrases, but on special occasions whistles were used. For example, a dignitary of the Havana lodge Biabanga was said to have “substituted his oral chant for the notes of the pito (reed flute) . . . in the beromo or procession.”

MIGRATION

In 1886, with the foundation of the cigar-making company town of Ybor City outside Tampa, many Havana cigar workers migrated there, making it the larg est Cuban settlement in the United States. Many male tobacco rollers, but cer tainly not all, were Abakua members, as described by Gerardo Pazos “EI Chino Mokango,” a third-generation Abakua of Spanish descent. From Havana, he told me about his family members who escaped persecution by migrating to Key West and Tampa in the late nineteenth century;

My grandfather Juan Pazos (1864-1951) was born in the barrio of Jesus Maria, the son of a Spaniard. He was obonekue [initiate] of the lodge Ita Barako Efa [meaning “the first ceremony of Efa”].

Many Cuban tobacco rollers went to Tampa, Florida, and stayed there,including my grandfather’s brother, who was a member of the lodge Ekori Efa . They left during the persecution of the Abakua by the Span iards, and later by the Cuban government. Many left in schooners to Florida, because those captured were sent to Fernando Pa, Ceuta and Chafarinas. I knew several elder men of color sent there who told me their stories. They were very tough prisons and many Abakua who were deported there died.

My grandfather’s brother lived in Tampa, and he never told me that they “planted” [initiated] in Florida. No Abakua elder ever told me that they “planted” there. While there are written histories of Cuban tobacco rollers in Florida, there is no history of Abakua in Florida, precisely because there has been no Aba kua ritual activity in Florida. Likewise, many narratives of Abakua in Spanish West African penal colonies where Cubans were imprisoned have been lost because they were not tied to the foundation of new lodges; when the colonial wars were over,the populations dispersed, often returning to Cuba. Cubans have come to Florida since the late nineteenth century to the present due to political, economic, and personal reasons. The recollections of Cuban Abakua regarding Florida remain vivid because of that region’s proximity to Cuba and the continual communications between family members.

Confusion in the Published Literature

Abakua leaders report that even though Abakua leaders lived in Florida, they could not conduct ceremonies, because there were no lodges there with the knowledgeable personnel and ritual objects. Nevertheless, a series of scholarly essays have claimed that Abakua lodges existed in Florida. For example, in 2001 Cuban scholar Enrique Sosa argued for the “certainty of the existence of fidfiigos” in Key West in the late nineteenth century among exiled tobacco workers.14 Sosa uncritically cited an earlier scholar who wrote: “Imported from Cuba, Nanigo appeared in Key West as a religious, fraternal and mutual-aid sect among blacks in the period 1880-90. The last Nanigo street dance occurred on the island in 1923.”For her evidence, this scholar cited Stetson Kennedy’s 1940 WPA report:

A Nanigo [sic] group was organized in Key West, and enjoyed its greatest popularity between 1880 and 1890. They gave street dances from time to time, and dance-parties on New Year’s . . . . In 1923 the last Nanigo street dance to be held in Key West was performed “for fun” by Cuban young people,attired in make-shift costumes.

Leader of the Nanigos in Key West was a man named Ganda, a small “tough” Cuban mulatto.. . . Ganda conceived the idea of making elabo rate Nanigo costumes, head-dresses, bongos (drums), and other equip ment, teaching young Cubans in Key West the Nanigo dances, and then joining his company with a carnival of some sort…. He finished the costumes and other equipment, but died in 1922 While Kennedy did not give evidence for the foundation of Abakua lodges there-he merely described costumes and recreational dances-later authors cited his work as evidence. In Havana, Gerardo Pazos “El Chino Mokongo” explained that Kennedy’s description was not that of an Abakua rite: “It is not possible even that they left in beromo [procession], without planting [a cer emony]. It is possible that comparsas [carnival troupes] paraded around with representations of Abakua with similar costumes and rhythms, but this is not Abakua ceremony.”l7 To perform an Abakua procession requires the authoriza tion of lodge leaders as well as access to their ritual objects.

Any expression of Abakua in Florida would only be in remembrance of Cuban ceremonials, in themselves a remembrance of Cross River Ekpe events. Kennedy reported to me that he spoke little Spanish at the time of research and had no proof of the society existing in Key West. Instead, he gathered recollections among exiled Cubans about the society as it existed in Cuba. Nevertheless, Kennedy’s work inspired later scholars as well as an official Flor ida guidebook that appears to be based upon his work:

From Cuba . . . the Latin-Americans of Ybor City and Tampa have im ported their own customs and traditions which survive mostly in annual festivals. The Cubans found good political use for voodoo beliefs brought by slaves from Africa to the West Indies and there called Carabali Apapa Abacua [voodoo being used generically for “African spirituality”J. Prior to the Spanish-American War [Cuban Wars of Independence], Cuban na tionalists joined the cult in order to hold secret revolutionary meetings, and it then received the Spanish name, Nanigo [an Efik-derived termJ.In 1882, Los Criminales de Cuba , published in Havana by Trujillo Monaga, described Cuban Nanigo societies as fraternal orders engaged in petty politics. Initiation ceremonies were elaborate, with street dances of voo doo origin. Under the concealment of the dances, political enemies were slain [a confused reference to carnival]; in time the dance came to sig nify impending murder, and the societies were outlawed by the Cuban Government [could be either a reference to Abakua, outlawed in 1875; to King’s Day processions, outlawed in 1884; or to carnival processions, outlawed in 1912. When the cigar workers migrated from Cuba to Key West and later to Tampa, societies of “notorious Nanigoes,” as they were branded by Latin opposition papers, were organized in these two cities . The Nanigo in Key West eventually became a social society that staged a Christmas street dance . . .. the last of the street dances was held in 1923 Nanigo, like voodoo, is simply a buzzword for unassimilated black people.

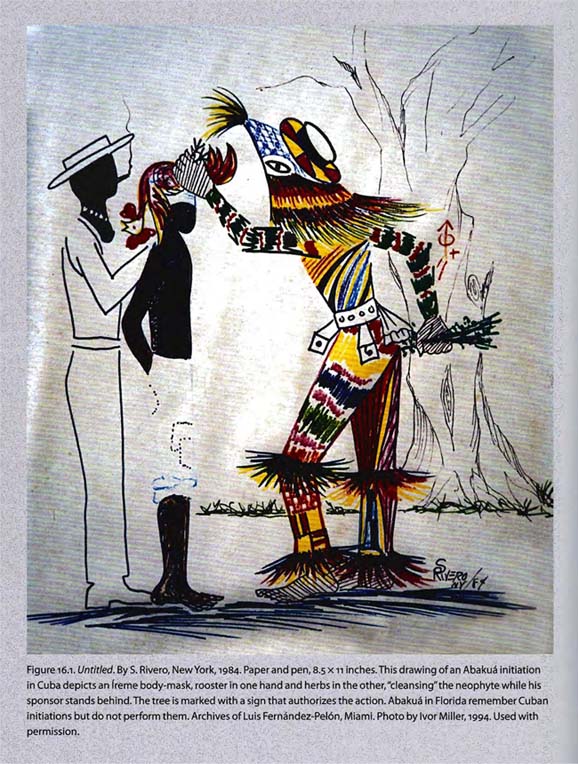

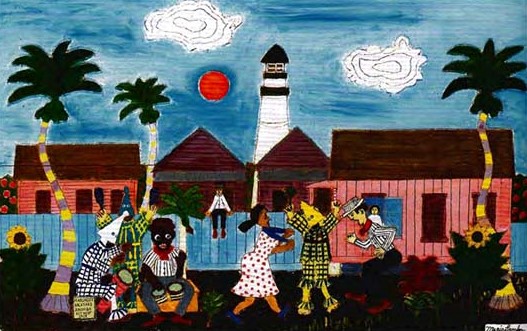

The claim of “societies of ‘notorious Nanigoes'” was partially inspired by depictions of carnival dance with body-masks by Key West artist Mario Sanchez (b. 1908 in Key West) (fig. 16.3) . Such depictions were misconstrued as evidence for Abakua ritual activity,when in fact they merely represented popular dances like rumba and carnival groups. (Sanchez’s work will be discussed in a later section.)

Historian Louis A. Perez Jr.-coauthor of Tampa Cigar Workers and author of several histories of Cubans in the United States- reported to me: “I have not come across any Abakua references in Tampa during the late nineteenth and early twentieth-centuries.” Anthropologist Susan Greenbaum wrote More Than Black: Afro-Cubans in Tampa , a study involving the mutual-aid and Cuban independence group the Club Marti-Maceo in Tampa. She wrote to me that during her fifteen years of research, “Nanigos were the subject of hushed and infrequent references. There could have been an active Abakua under ground here, but I never heard of it.”

Nevertheless, Cuban scholar Sosa argued for the existence of Abakua lodges in Florida by referring to an essay by Jose Marti (1893) titled “Una orden secreta de africanos” (A secret order of Africans) that described exile Tomas Suri in Key West. Sosa argued that Marti referred here to the Abakua (without mentioning them by name).23 Marti wrote that Suri belonged to “a tremendous secret order of Africans . .. a mysterious, dangerous, terrible se cret order,” but described an order of Africans where members rejected use of a drum, wanting instead to create a school,24 This could not have been an Abakua lodge, however, because without the consecrated drums there can be no lodge.

Marti may have referred to a group akin to Masons whose members included Abakua, but his message is ambiguous.In turn, Sosa’s erroneous essay was cited uncritically by Ishemo, who wrote: “Jose Marti appreciated the patriotism and the financial contribution to the war effort made by the Abakua cigar workers in Key West, Florida. He relates his visit to a fuifligo famba (a sacred room in the temple) and described it as ‘a room which is decorated with the flag of the revolution.” None of the sources cited confirm this statement. The “secret society of Africans” as described by Marti required that the holder of the “third grade” be able to read. This cannot be Abakua; grades are not numbered, and there is no such requirement. Most recently, a scholar wrote that “Potencias [Abakua lodges] were also established in the United States in the nineteenth century by Afro-Cuban mi grant workers in Florida.”27 An attempt to verify the source of the citation proved that it too was a misquote.

EVOKING ABAKUA IN MIAMI

Among the significant cultural achievements related to Abakua in Miami were the publications of Lydia Cabrera (1900-1991), who did extensive research in Havana and Matanzas from the 1930S to the 1950S. Her publications are the most relevant for the history of Abakua, as well as other African-derived in stitutions such as Lukumi and Pal Monte.

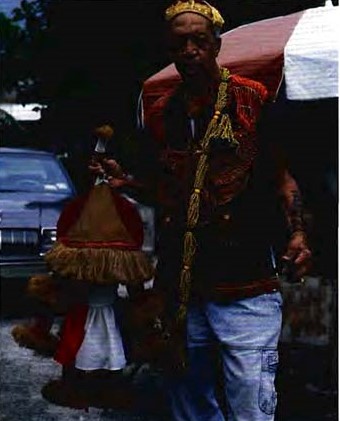

Cabrera left Cuba in the 1960s to settle in Miami, where she published a series of volumes documenting oral narratives of the African-derived traditions of Cuba, including monumen tal studies of Abakua drawn esoteric signs (1975) and language (1988), each about five hundred pages, without which the study of Abakua would be nearly impossible. In 1994,in Miami, I met Luis Fernandez-Pel6n “EI Pel6n,” a titled Abakua member who was recommended by my teachers in Havana (fig. 16-4). Regard ing Abakua activities in Miami, he told me: “Here in Miami there are ceiba [kapok] and palm trees, but since the most important thing-the funda mento-ran object with ritual authority] is in Cuba, no Abakua group can be consecrated here. I have met with all the Abakua who live here and we have had celebrations with my biankom6 [drum ensemble], but no consecrations.”Unlike the sacred objects of other Cuban religions of African descent, those of Abakua are thought not to have left the island. Nevertheless,in 1998 the “birth” of the first Abakua group in the United States was announced in Miami. It was named Efi Kebliton Ekuente Mesoro,a reference to Efik Obliton, the first lodge established in Cuba in the 1830S,itself named after Oblitong, a community in Calabar. The event took place on January 6, considered the anniversary

of Abakua’s foundation in Cuba. The would-be Miami founders sent a letter to Abakua leaders in Havana, announcing their existence. The Abakua leaders I spoke with in Havana unanimously considered it a profanation: the “birthing” of an Abakua group without a sponsor is not valid. Additionally, they observed that many of these same Miami leaders had been previously suspended from their Cuban groups for disobedience, and hence had no authority to act. Gerardo Pazos “El Chino Mokongo,” who was also a babalawo (Yoruba Ifa diviner), told me: It is not possible that a lodge was created in Miami, because no Cuban there has the authority or knowledge to perform the required transmis sions. Whoever would create a lodge in Miami would have to come to Cuba and carry a fundamento [sacred objectl from there. It is not the same with the Yoruba religion [which does travel]. We cannot predict the future, but until now there is no Abakua in Miami or anywhere in the USA who has sufficient knowledge to create a new tierra [lodgel. In this moment, September 27, 2001, there is no Abakua in the USA who knows enough of the [rituallianguage required to make the transmissions. Be cause I, Gerardo Pazos, Mokongo of Kamaroro, do not know anyone with enough knowledge to create a lodge. According to Cuban lore, Abakua lodges were established in Havana and Matanzas by knowledgeable Cross River Ekpe leaders who had the authority to do so. Since Ekpe leaders could not return to Africa, they moved forward and created. But Abakua members living outside of Cuba can return to consult with their elders to seek possible authorization to establish new lodges. “EI Chino Mokongo” continued: Those Abakua who have migrated to the USA do not have the knowledge to create a Potency [lodge] there, because this process requires many men with knowledge and because these ceremonies are very profound. In addition, when a Potency is created, one must pay the derecho [fee] of one rooster to all the existing Potencies in order to be recognized by them. If a juego [lodge] is born in Havana, it must pay this fee to the other juegos in Havana. If it is born in Matanzas, then to the others in Matanzas. The juego they tried to create in Miami had no godfather [sponsor], and furthermore, it did not have the knowledgeable men to found it. It cannot exist. “El Chino Mokongo’s” statement reflects not only his personal views but the protocol followed by all Abakua leaders on the island.